Our Director Tina reflects on spending Christmas volunteering with people seeking sanctuary in Northern France.

I returned to volunteer in Calais for two weeks over Christmas and New Year with Refugee Community Kitchen, spending long, busy days washing, chopping, slicing, peeling, preparing and distributing hundreds of meals. Every week day we travelled to two sites in Calais and prepared food for another organisation to distribute in Dunkirk. On Christmas morning, we paused the washing up and cooking long enough to celebrate with pancakes and a multitude of toppings — a joyful Christmas Day breakfast! I was also thrilled to hear the Green party leader Zak Polanski’s Christmas Day message, recorded during his recent visit to Calais. It was heartening to see a politician shining a light on what is happening there.

The weather on the French coast is notoriously bitter- biting wind, freezing rain. Not the time to be living in a flimsy tent and sleeping on the ground – yet hundreds are. News articles are quick to report the numbers of boats arriving but little is reported about the misery behind the number crunching; an absence of boats crossing is interpreted as hostile policy success but in reality this is predominantly because conditions are too cold, too windy, too brutal. Which means people are stuck in their tents, waiting the weather out.

I spent a weekend volunteering with Roots run by my old friend Tom, an organisation supporting hundreds of people in Dunkirk. The brutality of the weather there was immediately apparent. The showers they had installed on a piece of wasteland — using upcycled IBC water tanks to create shower ‘cubicles’ — were unusable because the pipes had completely frozen. It felt painfully ironic: when people most needed a hot shower to thaw out, they couldn’t access one.

Instead, people huddled in the ‘Hub’ — four gazebos erected daily side by side — sheltering from the wind, charging their phones, enthusiastically (and very competitively!) playing Connect 4 and competing to see whose phone could connect to the speaker so they could play music they liked. A screen hung at one end, and people sat on an extremely uncomfortable wooden bench to watch something on Netflix — a small distraction from the howling wind and cold outside. A young boy, aged no more than 8 tugged at my sleeve and asked if he could watch the Transformers Movie. Like many little boys on Boxing Day he wanted to watch his favourite film; but the similarities ended there.

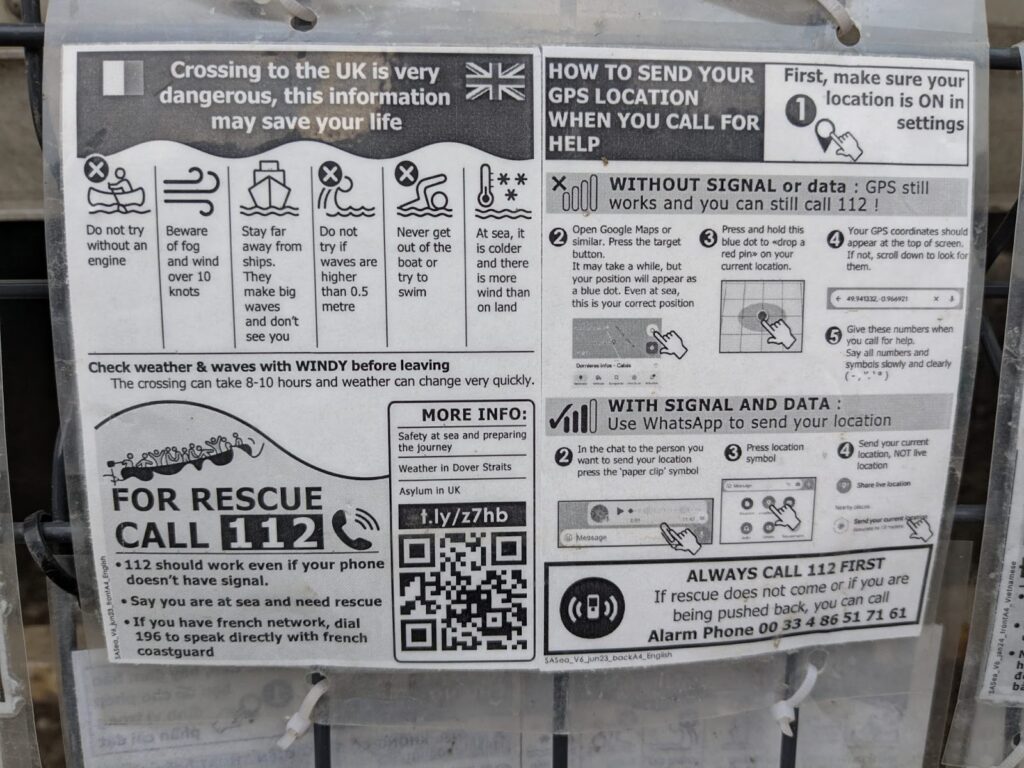

Roots display an information stand every day, translated into a multitude of languages. One of the flyers outlines safety warnings about crossing the Channel. Although I thought I was relatively well informed, I was shocked to read that the crossing can take eight to ten hours — in the dark, trying not to be spotted while also dodging huge ferries in one of the busiest stretches of water in the world. All of this while sitting in an open-topped, overcrowded boat, with no protection from the elements. I cannot imagine the fear and the cold that accompanies every minute of that journey.

The December 2025 “You Can’t Stay, You Can’t Go” report by the Humans for Rights Network documents the daily state-sanctioned violence faced by people at the Calais border — raids, destruction of shelters and harassment — all sanctioned under official policies. Since 2018, the UK government has pledged at least €763.4 million to the French government to ‘secure’ the border, funding the very mechanisms that keep people trapped in this cruel, endless waiting. It is a system that denies safety in France while making the UK unreachable, leaving people exposed to constant fear, uncertainty and desperation. Meanwhile, the French government spending focuses on violent policing (85%) rather than the reception of people at the border (15%). I recommend reading the Executive summary of this report to understand the human experience behind the ‘small boats crisis’ headlines.

Just this week in Bradford, I met someone who had made the perilous journey through Dunkirk. Moments like that remind me that being an ally isn’t only about supporting people once they arrive — it’s also about knowing, even in small ways, what they have endured to get here. Understanding something of that journey, and the trauma it involves, helps us meet people with dignity and respect.

I spent nearly two years in Calais between 2015 and 2017. While this place remains full of human misery, desperation and exploitation, it is also sustained by volunteers who have been turning up from across Europe for over ten years — thousands of allies giving their time, offering kindness, and refusing to look away. As in Bradford, Calais is a place of extremes: immense hostility, divisive policies and violent rhetoric — and, alongside it, compassion in abundance and hope being built day by day.

I washed up next to John, a beautiful, kind man who had driven from Bavaria to volunteer in Calais. His silent tears spoke volumes. Sarah from England has been a team lead for Refugee Community Kitchen for six years. Their ally-ship is visible in being present and bearing witness in a place where people are meant to be unseen.

I am continually humbled and inspired by the community of allies — in Calais and Bradford — who show up, speak out and stand together. When systems and policies are deliberately designed to dehumanise, choosing care, presence and solidarity — even quietly, even invisibly — is an act of radical resistance.